The 40-Camera Robot That Always Gets a Reaction

What happens when you give a machine too many eyes.

Whenever I introduce myself and I want to make an impression, I talk about a robot we built for an agricultural field. It didn’t have much autonomy—my area of expertise—but I still bring it up for one specific reason.

It had 40 cameras.

People don’t say “wow” out loud, but I can see it in their eyes. Cameras just do something to people. There’s something about robots that can see that makes them feel more alive, more intelligent—even when they’re not autonomous at all.

It’s a little trick I’ve learned: if I want someone to perk up when I say “robotics,” I just say “we strapped 40 cameras to a robot in a sorghum field.” And then they’re all ears.

So now that I have your attention, let’s talk about what this robot actually did—and what it taught me.

Inside the Robot: Building a Plant-Scanning Beast

We built the robot to do something called high-throughput phenotyping. The goal was to scan rows of energy sorghum plants and generate 3D models fast—at field scale. Traditional phenotyping is slow, manual, and subjective. We needed something faster, repeatable, and more precise.

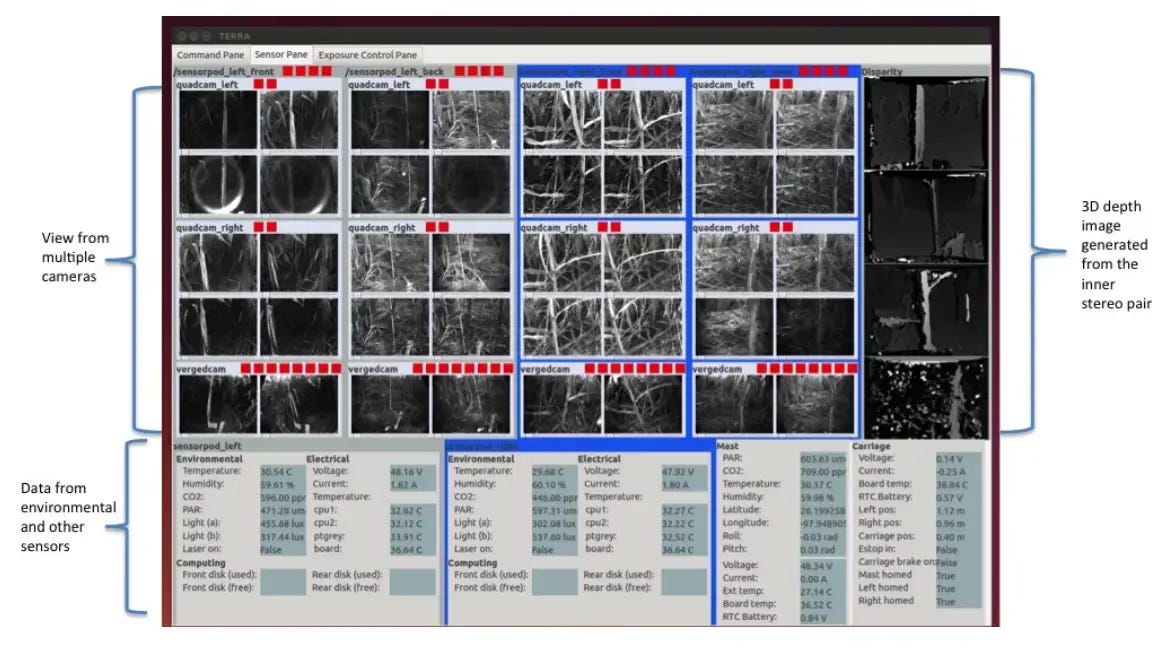

The machine had a vertical scanning arm with a sensor pod mounted at the end. On both sides of the pod: banks of cameras. As the arm moved through the plant rows, it captured hundreds of synchronized images from multiple angles.

Why so many cameras? Two main reasons:

Spectral diversity – Some cameras captured images at different wavelengths. We were looking for subtle traits in the plant’s structure or stress levels that show up beyond visible light.

3D reconstruction – With enough overlapping views, we could use stereo vision and structure-from-motion (SfM) to generate point clouds of entire plants.

Sounds straightforward, but plants are a nightmare for 3D reconstruction. They move. They flex. Their leaves are thin, reflect light weirdly, and overlap unpredictably. Traditional stereo algorithms struggle in such environments.

One thing we learned fast: timing is everything. To minimize motion artifacts, we had to fire all 40 cameras at precisely the same instant. Getting the exposures right, ensuring calibration, making sure all the data was logging correctly—that alone was a major engineering effort.

We ran two full field deployments. Just those two runs generated 4 terabytes of data.

I led the software stack, helped bring the system online, and ran field ops. It was intense, exhilarating, and completely different from anything I’d done in a lab.

Lessons That Changed My Thinking

This project pushed me out of the clean, structured world of lab robotics and into the chaotic, unpredictable, and sensor-unfriendly world of agriculture.

It also shifted my thinking in two big ways:

First, I gained a deep respect for how little of the real world fits inside our models. The environment is never static. Plants sway. Lighting changes. Dirt gets on the lenses. The field throws problems at you that the lab never prepared you for.

Second, I realized how little robotics had touched agriculture—despite its massive impact potential. It’s easy to demo a robot on flat ground. It’s much harder to deploy one in a crowded field of tall, moving, lookalike plants under harsh sunlight and zero connectivity.

Since then, I’ve watched the field mature. More researchers, startups, and companies are beginning to embrace these harder challenges. Robotics is slowly moving from the warehouse to the wild.

But the lesson remains: the real learning happens in the field.

What I’d Do Differently Today

This project happened a few years ago. If I were building this system today, I’d probably still use a lot of the same hardware principles—but I’d rethink the software stack entirely.

In particular, I’d skip traditional stereo matching and jump straight to modern foundation stereo models like NVIDIA’s Neuralangelo or similar approaches. These models can reconstruct dense point clouds even in cluttered, low-texture, or non-rigid scenes. They outperform classical SfM in both fidelity and robustness.

But more than anything, I’d be even more obsessive about making the system field-ready from day one. You can’t fake robustness when the ground is bumpy, power is flaky, and your robot is baking under the sun.

This is what excites me now: real-world, imperfect, messy robotics. The kind that breaks and teaches you something every time you take it outside.

If you liked this kind of deep dive—equal parts engineering, storytelling, and real-world lessons, subscribe to so you don’t miss the next one.